How I Stopped Worrying (Mostly) and Learned to Fill My Own Rebreather Oxygen Bottles

Rebreather diving, has yet to capture the popular imagination. As of 2023, it’s estimated that there are roughly 30,000 active rebreather divers worldwide. By contrast, some 6 million people still rely on traditional open-circuit SCUBA, and PADI, the largest certification agency, has churned out 27 million divers since 1967. What all this means is that if you walk into your average dive shop and say, “I need an oxygen fill for my rebreather,” you will likely be met with the same reaction you’d get if you had requested a live giraffe.

Undeterred, I began my quest for oxygen. The local dive shop politely but firmly refused. Medical oxygen suppliers seemed convinced I was up to something nefarious and possibly combustible. The local welding supply shop had plenty of bulk O2 but no means to transfer it into my modest little three-liter bottle. What I needed, it turned out, was a booster pump, some oxygen-clean hoses and fittings, and a drive gas source to make the whole thing work. What I didn’t need, but got anyway, was a creeping sense that I was embarking on something mildly illegal, possibly dangerous, and almost certainly ill-advised.

Naturally, I turned to the internet, where you can, in theory, learn anything. Unfortunately, my search results mostly made me feel like I was either about to blow up my garage or become the subject of a niche episode of CSI: DIY Disasters. The best resource I found was a book with the wonderfully disconcerting title The Oxygen Hacker’s Companion by Vance Harlow. Nothing about that title inspires confidence, but the book was an invaluable guide to handling high-pressure oxygen without inadvertently becoming a cautionary tale.

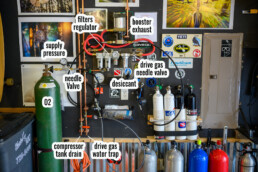

After much reading (and some light soul-searching), I settled on the USUN XB30-OL booster, a hose kit from Dive Gear Express, and an entry-level Husky air compressor from Home Depot, along with some basic drive gas filtration and a desiccant dryer. You can save a few bucks by sourcing your own hoses and adapters, but I decided that buying a pre-made whip might slightly reduce the chances of blowing up my garage.

Naturally, the setup evolved. Over time, I modified the Dive Gear Express whip by removing the inline valve at the fill end and replacing it with a Hoke needle valve on the supply side. This decision was inspired by a deeply unsettling Facebook post featuring a photo of an inline valve that was accidentally left closed, and after a few booster cycles, decided it had had enough and dramatically exploded. That, I thought, seemed like a situation best avoided.

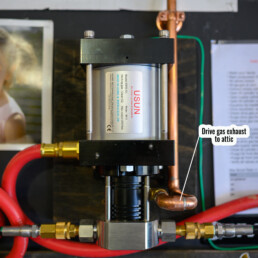

Another minor improvement involved dealing with the unspeakable racket the booster made every time it cycled—roughly every three to four seconds when boosting O2. This was less of an issue in the sense of ear protection (which was mandatory) and more of an issue in that with ear protection on I had no chance of hearing gas leaks if something were to go awry. After a surprisingly responsive email exchange with USUN—who, despite being on the other side of the world, replied faster than my own kids—I rerouted the drive gas exhaust into my garage attic. A bit of leftover ½-inch copper, a few easy modifications, and voilà: blissful near-silence.

The compressor itself, a valiant, cheap little Home Depot workhorse, has held up well. It works hard at higher boost ratios, but so far, it’s remained within its rated 50% duty cycle and has yet to catch fire, which I count as a win. It is, however, absurdly loud. So, like the boost exhaust, I simply moved it to the attic. This had the unintended but welcome side effect of turning the long copper supply line into a cooling mechanism, allowing hot gas to condense and shed moisture before reaching the booster. As I understand it, water in the booster is bad, and as the rebreather business is expensive enough, I’d prefer to keep things working as long as possible.

All in all, I’m quite pleased with how this setup has come together. It is now quiet, efficient, and, to the best of my knowledge, reasonably safe—though, as The Oxygen Hacker’s Companion makes abundantly clear, safety in these matters is largely dependent on the intelligence and attentiveness of the operator. So, if you’re considering doing something similar, I highly recommend reading that book before even thinking about touching an oxygen booster.

And if I’ve overlooked some glaring safety hazard or accidentally constructed a small-scale doomsday device, please, please let me know.